Disc golf is a growing sport—largely because it’s almost obnoxiously accessible.

You can head to a local park, grab a disc, and start throwing it toward a metal basket. That’s pretty much it. There’s something fascinating about how little you need to get started: a disc, a target, and a patch of land. Compared to other sports, the infrastructure is almost nonexistent. Golf requires manicured fairways, greens, and tee boxes. Soccer demands an acre of flat, open field. Disc golf? It can be played in a forest, a hillside, or a city park with minimal intervention.

Even at the sport’s highest levels, the built requirements are humble: a 3-by-6-foot concrete tee pad and a $300 steel basket mounted on a single metal pole set in a small concrete footer. In its earliest days, the tee was just a mark on the ground and the target might have been a tree. The game has evolved, but the spirit remains: minimal impact, maximum play.

This ability to adapt to nearly any topography or climate is part of what makes disc golf compelling—and, for me, connects it to some of the 20th century’s most interesting architectural thinkers.

The most immediate link is in the design of the disc golf basket itself. A metal ring suspends chains downward into a basket, all supported by a single vertical pole. That one contact point with the Earth is intentional. It’s easy to install—just a pole, a bag of Quikrete, and some effort—and equally easy to remove. But it also serves a deeper purpose: it minimizes interference with the space around it, letting discs fly past with no walls to catch errant throws. The result is a structure that exists within nature without dominating it.

Playing disc golf often feels like a nature hike punctuated by moments of focus. It’s the kind of experience architects like Le Corbusier and Buckminster Fuller dreamed about—inhabiting the land lightly, with reverence and restraint.

Le Corbusier, in his Five Points of Architecture, famously proposed lifting a structure above the ground on pilotis to allow the landscape to continue beneath it. Buckminster Fuller took that further. Best known for his geodesic domes—like the one he designed for Expo 67 in Montreal—Fuller was obsessed with lightness, efficiency, and systems thinking. He believed that the Earth itself was a spaceship with limited resources, and any additions to it should be efficient and non-invasive.

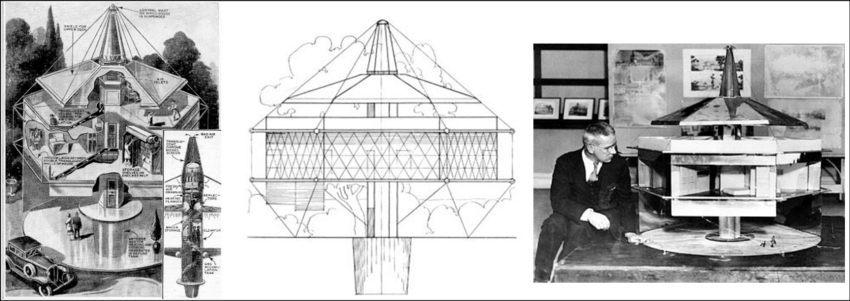

One of his lesser-known projects, the Dymaxion House, encapsulated these ideas. Designed to be mass-produced, shipped anywhere, and installed on any site, the Dymaxion House sat elevated on a central column that housed all the mechanical systems. Living spaces wrapped around this core, offering panoramic views while barely touching the ground. It was a vision of a future where dwellings could appear anywhere—light, efficient, and environmentally considerate.

And somehow—through culture, economics, and grassroots enthusiasm—disc golfers have stumbled into a parallel philosophy. They play in woods, over hills, through parks. They hike, they aim, they throw. And their target is a tiny intervention: a basket on a pole, barely touching the Earth.

Leave a comment